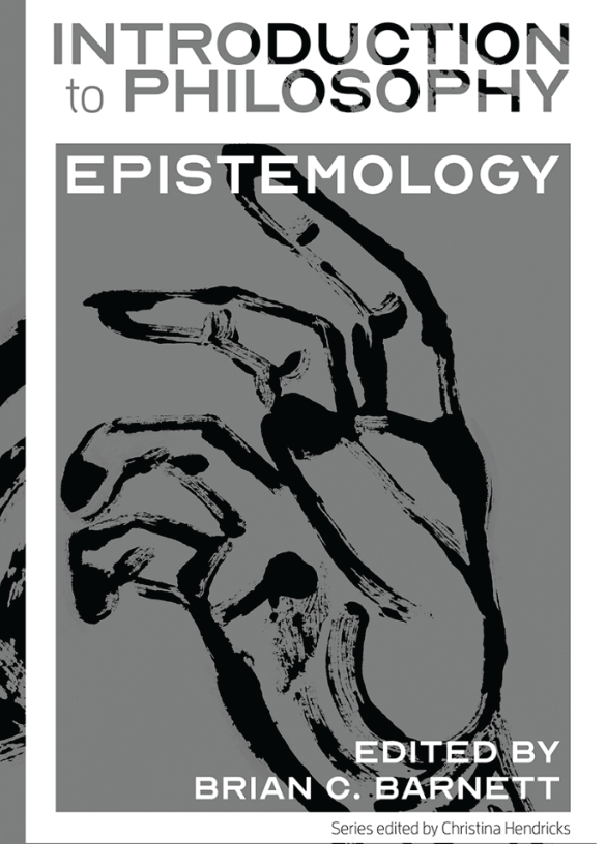

Heather Salazar was kind enough to create the cover art for the Introduction to Philosophy series. Her wonderful piece for this book, titled Here Is a Hand, was inspired by G. E. Moore’s famous “Proof of an External World” from his 1939 essay by that title. Moore’s “proof” is featured in Chapter 4 of this volume. The cover design for this book and others in the series is by Jonathan Lashley.

Knowledge is the central concept of traditional epistemology. But what is knowledge? This is the most basic question about the central concept, and so the appropriate starting place. Answers traditionally come in the form of conceptual analysis: a set of more basic concepts out of which the analyzed concept is built, arranged to form a definition. The concept “square,” for example, is analyzable into components such as “four-sided figure,” “right-angled,” and “equilateral.”

1 Our focus here is the analysis of knowledge. But we’ll also consider critiques of this focus, which yield useful insights and prompt new directions of inquiry. The chapter closes with a reflection on the value of epistemological conceptual analysis.

What the first three have in common is that they require direct experience with their objects. I know how to ride a bike because I’ve had practice; I don’t know how to fly a plane, since I lack training—despite having memorized the manual. Plato knew Socrates and Athens because he studied under the man and lived in the city; Plato knew neither Homer nor London because he neither met the poet nor visited the place. Plato knew of Homer, and propositions about him, but nothing concerning London. Stella knows what strawberries taste like (having eaten them before), but not what it’s like to be a bat given her lack of batty experiences (see Box 1).

In his influential 1974 paper “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” philosopher Thomas Nagel explains that for something to be conscious, “there is something it is like to be” that thing—“something it is like for” that thing to be (436). Thus, consciousness essentially has a “subjective character” in that it requires a first-person “point of view.” As such, no conscious state can be fully grasped or explained from the purely objective third-person perspective (nor from a God’s eye “view from nowhere”). From this, Nagel draws a metaphysical conclusion: that the mental cannot be reduced to the physical. More pertinent to this chapter is an important epistemological implication: that we cannot know “what it’s like” to have experiences that are radically unlike those we’ve actually had. He uses his now-famous bat example to illustrate:

Bats, although more closely related to us than those other species, nevertheless present a range of activity and a sensory apparatus so different from ours that the problem I want to pose is exceptionally vivid (though it certainly could be raised with other species). Even without the benefit of philosophical reflection, anyone who has spent some time in an enclosed space with an excited bat knows what it is to encounter a fundamentally alien form of life.