The foundations of engineering practice are mathematical models, the principles of physics, and empirical results obtained from experiments for defining design criteria. An engineer must know the laws of physics very well and use the relevant mathematical models and their solutions, either exact or numerical, to design parts, systems, and complex machines which function with certain reliability for an assumed lifetime. To help with this task, an engineer may use modelling tools to simulate the behavior of systems and their components. Modelling and the application of software tools are becoming increasingly common in modern engineering practice. As shown in Figure 1‑1 1, modeling and simulation results can help optimize and refine a design before the physical prototype is built. This minimizes the time required for the design process. In addition, application of modelling can minimize the final cost of a prototype or a product.

Modelling has a long history starting from ancient times when scientists used “equations” to relate variables or parameters to one another (e.g., Archimedes, Thales, Khawrazmi). Later, scientists and mathematicians developed “equations” which could represent the way that natural phenomena work and materials behave. These “equations” are sometimes referred to as laws of physics and constitutive equations since they are validated through time and the obtained results match with what we experience or measure in the real world with some approximations, of course. For example, Newton’s second law is given as a model which predicts the behaviour of material bodies under given forces applied to them, i.e., the relationship between forces applied to a body mass and the change of its momentum with respect to time.

Similarly, Ohm’s law is a model which relates the voltage across a resistor to the electrical current using the resistor’s material property. These models, and many other similar ones (e.g., Hooke’s, Fick’s, Fourier’s) related to different engineering disciplines, form the foundation of engineering. It is through their application that we trust the behavior and responses of our designs in the real world. Assume that we are flying in an airplane which is designed based on laws and governing equations or models applied to fluid mechanics and solid mechanics, among others. If we don’t trust and accept these laws and models, then it would not be logical to ride in an airplane!

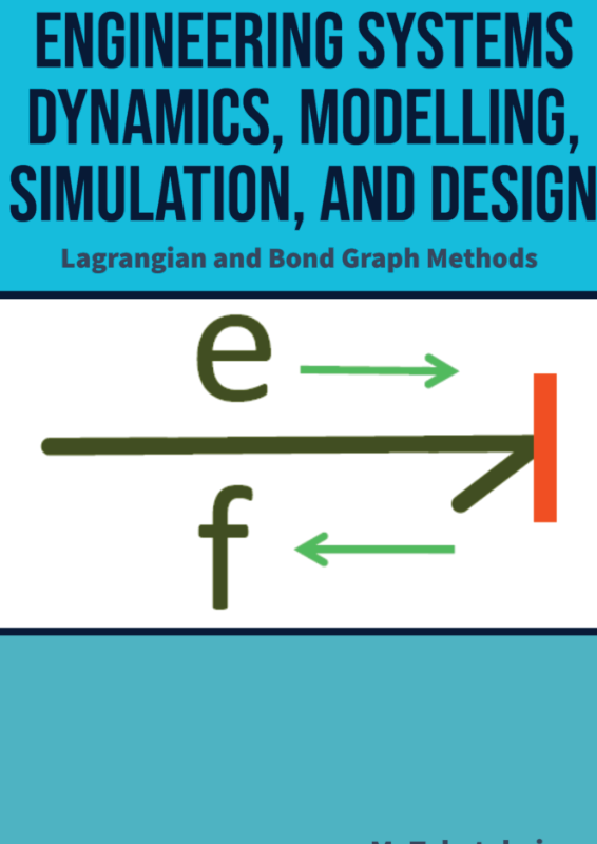

Real-world phenomena are complex and usually involve many types of physics. For application in engineering, we usually simplify these phenomena and consider the dominant physics involved. For example, the length of a simple spring linearly changes under a given load according to Hooke’s law. But it becomes a more complex problem if the spring’s material behaves non-linearly, or if for example, electrical charges flow through it. Traditionally, the simplification of a problem is/was due to lack of tools for finding a solution which could represent more accurately that problem’s real world behaviour. It is at this point that modelling methods, e.g., Lagrangian and BG, and advanced modelling software tools, e.g., 20-sim, are valuable resources for finding solutions to complex engineering systems and optimizing our designs to have more Henry Paynter (1923–2002). Courtesy MIT Museum.

economical, reliable, and durable products as end results. Although this book focuses on using bond graphs as a modelling method, we also emphasize the importance of learning and, hence, understanding the foundation and mathematics behind an energy-based approach for system analysis. For this purpose, we summarize Lagrangian mechanics in chapter 2 and provide some references for further reading.