This working paper on occupational safety and health in forestry is intended for an audience of producer organizations, trade unions, vocational training institutes, extensionists, instructors and relevant public bodies. It is also meant to serve as an introduction to the subject for foresters who have had little or no exposure to the subject.

Workplace conditions in forestry – both silviculture and harvesting – are a function of site conditions, climate, weather, terrain and tree characteristics. Forestry is one of the most dangerous work sectors. While reliable global statistics on accident and fatality rates are missing, the available data clearly indicates that forestry is a high-risk occupation. Even among trained forestry professionals, the risk of accidents is high. Farmers and other self-employed forest workers appear to be at even greater risk. One reason for this is that they only undertake forestry work or use forestry tools on an ad hoc basis and lack sufficient safety training, experience and knowledge.

This cannot, however, be used as an excuse to simply accept poor safety records. Much can be done to establish a safety culture that minimizes risks to worker safety and health.

A sound safety culture recognises that accidents will likely occur. The challenge is to reduce or avoid the consequences of such accidents. There is much that can, and must, be done to establish a safety culture in forestry.

The fundamentals of accident prevention are reduced hazard exposure and worker safety training. The first is often achieved through risk assessments to identify hazards and take action to minimize or, in a best-case scenario, eliminate them from the workplace. Although some hazards are intrinsic to forestry work, risks are not.

Accidents will happen even in the best of circumstances. Individuals and teams should be prepared for accidents at all times. This extends beyond forestry sector employees; rural households with self-employed members should have a planned response to accidents.

This publication recalls that the purpose of accident analysis is to identify what occurred, the causes of the accident and the ways in which similar accidents might be avoided in future. Reporting near misses is critical, because it provides information on hazardous behaviour and unsafe working methods and equipment that can be used to reduce the potential for future accidents.

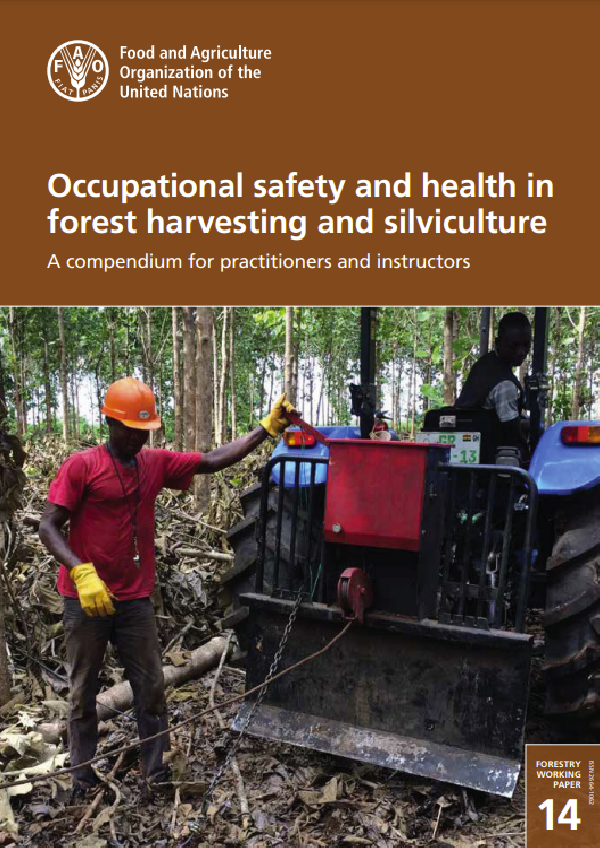

When a hazard cannot be removed or controlled sufficiently, personal protective equipment (PPE) may be used. This equipment and clothing protects against health and safety risks at work. It includes items such as safety helmets, gloves, eye protection, ear protection, high-visibility clothing, safety footwear and respiratory protective equipment (RPE).

Child labour is a human-rights issue and of obvious relevance to occupational safety and health. Reliable data on child labour in forestry is almost completely absent. Evidence suggests that children are particularly engaged in harvesting of non-wood forest products (NWFPs). Tree climbing is a major hazard. It is also likely that children work in nurseries, regeneration and stand tending. Children undertaking work is not inherently undesirable. Age-appropriate tasks that allow children to gain skills can be beneficial to their social development. Moreover, these activities may contribute to the household economy. What exactly is an age-appropriate task? National legislation may provide some guidance, but more operational guidelines are needed.

Women in forestry can, for reasons of physiological difference, be exposed more often than men to musculoskeletal disorders (e.g. carpal tunnel syndrome, tendonitis, etc.), respiratory diseases resulting from fire exposure, infectious and parasitic diseases, reproductive disorders due to chemical exposure, healthcare-specific incidents such as needle sticks, and anxiety and stress disorders. On average, women working in the forestry sector will have a working capacity one-third lower than their male counterparts, and this needs to be respected.

Heat stress occurs when the body is unable to dissipate body heat sufficient to its surroundings. Heat stroke is the most serious health risk posed by heat stress. It develops when a person works for a sustained period in hot conditions and becomes unable to continue sweating, and internal body temperature rises rapidly beyond 40 °C. Heat stroke is a medical emergency requiring immediate and qualified care. A person experiencing heat exhaustion is severely dehydrated and fatigued. Sufferers should be moved to a cool environment for rest and rehydration to restore their internal water balance. They should return to work only when fully hydrated, which may take up to 24 hours.

Risks and hazards associated with NWFPs differ from those resulting from timber harvesting. Hazards derive from activities like climbing, cutting with sharp tools, digging and gathering, picking, and long and/or heavy manual transport. The use of appropriate, well-maintained and sharp tools can mitigate cutting hazards. Proper cutting techniques will, of course, reduce risk. Training in planning, risk assessment and site preparation can also contribute to a safer work environment.