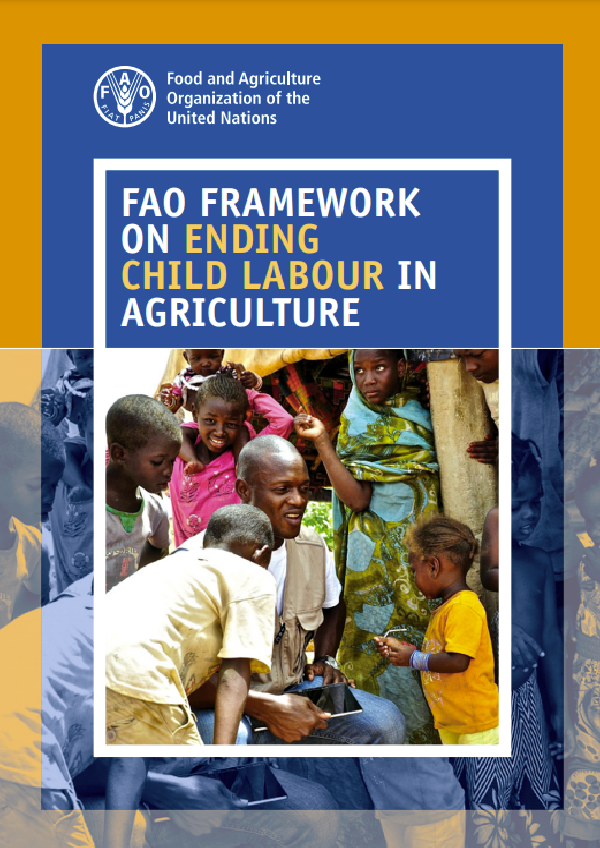

The purpose of the FAO’s framework is to guide the Organization and its personnel in the integration of measures addressing child labour within FAO’s typical work, programmes and initiatives at global, regional and country levels. It aims to enhance compliance with organization’s operational standards, and strengthen coherence and synergies across the Organization and with partners. The FAO framework is primarily targeted at FAO as an organization, including all personnel in all geographic locations. But the framework is also relevant for FAO’s governing bodies and Member States, and provides guidance and a basis for collaboration with development partners. The framework is also to be used as a key guidance to assess and monitor compliance with FAO’s environmental and social standards addressing prevention and reduction of child labour in FAO’s programming.

ENDING CHILD LABOUR WILL BE DECIDED IN AGRICULTURE

Eliminating child labour is a global priority, embedded in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8.7, which provides for the elimination of child labour in all its forms by 2025.1 The world will not be able to achieve this goal without the elimination of child labour in the sector of agriculture.2 Indeed, the International Labour Organization (ILO) 2017 global estimates show that child labour is overwhelmingly concentrated in agriculture. Of the 152 million children who are in situations defined as “child labour”, the vast majority – 108 million girls and boys between the ages of 5 and 17 – are to be found in farming, livestock, forestry, fishing or aquaculture (ILO, 2017a).

Ending child labour in agriculture is crucial for future decent youth employment opportunities, the reduction of poverty and the achievement of food security. It strongly interlinks with SDG 1 for poverty reduction and SDG 2 for food security and nutrition.

There is an economic case for ending child labour in agriculture. In 2004, an ILO study calculated that the costs of eliminating child labour worldwide would be in the area of USD 760 billion, while the benefits would be nearly seven times that – an estimated USD 5.1 trillion in the developing and transitional economies where most child labourers are found (ILO, 2004).

The need to address child labour within the scope of agricultural programmes can be approached from different angles:

Child labour is a human rights issue. All children have a right to childhood, including the right to protection from economic exploitation and from labour that jeopardizes their development, education or health. Children are not small adults: their bodies are developing and as such, they proportionally need more sleep and more water, and they inhale more often than an adult. A task that is innocuous for an adult can have a long-term negative effect on the physical and cognitive development of a child (FAO, 2019a). There is a shared responsibility to ensure that agricultural, food security and nutrition interventions do not cause any harm to children and offer sustainable alternatives to child labour.

Child labour is detrimental to children’s education, acquisition of higher level skills, health and nutrition,3 and it decreases their chances of accessing decent employment as youth and adults.

The children of today are the farmers, fishers, foresters and livestock raisers of tomorrow. Ending child labour in agriculture means building a safe path for girls and boys, providing them with a choice to contribute to society based on their individual capacity and interest, potentially empowering them to become active agents of the transformation and modernization of agriculture; reducing gender inequalities in agriculture, by paving the way for equitable socio-economic opportunities for boys and girls; supporting agriculture that can feed the world of tomorrow and preserve the environment.