In 2017 famine reared its head, but the international community gave generously and mobilized rapidly to successfully prevent its spread.

The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2017 reported both a rise in the absolute number of people affected by chronic hunger since 2014 and an increase in the global prevalence of undernourishment since 2016. Conflict is the main factor behind this rise in hunger, often exacerbated by severe climate events, like the continued drought in the Horn of Africa.

While old conflicts continued without any end in sight, new ones were sparked and millions of people fled their homes in a desperate search for safety, shelter and food. Yet, while we despaired of human capacity for violence, we admired the incredible generosity of neighbouring communities, themselves often struggling to survive, who welcomed them, shared their food and homes and did their best to provide immediate support to these displaced populations.

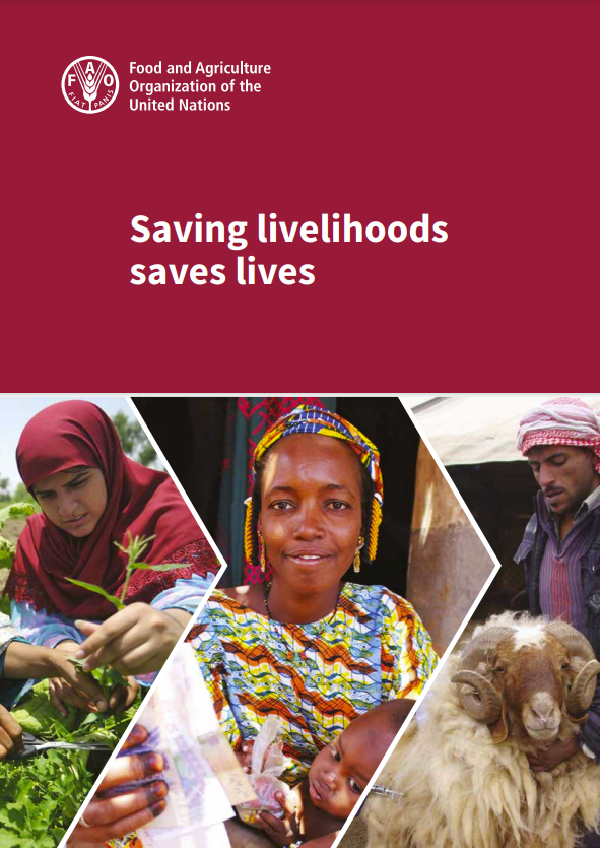

The document provides a summary of major achievements under FAO’s resilience programme, including emergencies, in 2017.

The year 2017 witnessed hunger on a scale not seen in decades. The Global Report on Food Crises 2017 indicated that 108 million people were facing severe hunger by the end of 2016 – up from 80 million the previous year.

Millions of people in northeastern Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan and Yemen faced the threat of starvation and, in February, famine was declared in two counties of South Sudan, affecting 100 000 people. The international community rallied fast, mobilizing more than USD 2 billion for the four countries on the brink, containing famine in South Sudan and averting a famine declaration in the other three.

Despite these efforts, the number of people severely food insecure – in Crisis Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC Phase 3) and Emergency (IPC Phase 4) – continued to rise throughout the year. Clearly, more needs to be done to address the steady rise in the number of people on the verge of catastrophe.

Continued conflict in Iraq, South Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic and Yemen, among others, and new outbreaks of violence in the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Myanmar contributed to increased displacement. In the Caribbean, hurricanes Irma and Maria devastated lives and livelihoods, while continued drought further eroded livelihoods in the Horn of Africa, where vulnerable pastoral populations were particularly hard hit. Across Africa, millions of smallholders’ crops have been threatened by the emergence of the fall armyworm.

Between 60 and 80 percent of these crises-affected people rely on agriculture for their livelihoods, they are farmers, herders, fishers and forest-dependent communities. In Somalia, for example, 90 percent of those in Emergency (IPC Phase 4) by mid-2017 were rural populations.

Investing in agriculture from the onset of a crisis saves lives and enables people to rapidly resume local food production and earn an income. Despite this, agriculture was one of the least-funded sectors of the 2017 humanitarian appeals.