This guest blog is by Mette Kia Krabbe Meyer, Research Librarian, Department of Maps, Prints and Photographs at the Royal Danish Library

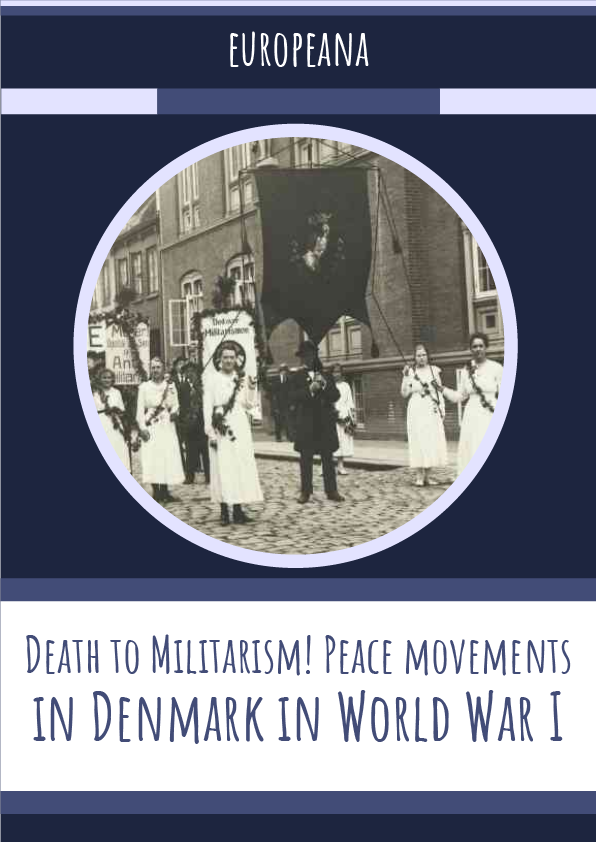

The Women’s Peace Party (later the “Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom”, WILPF), was founded in 1915 as a reaction to the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914.

This association was founded at the Women’s Peace Conference in The Hague, which was attended by several Danish women, including Thora Daugaard (1874-1951), Eline Hansen (1859-1919), Clara Tybjerg (1864-1941), Louise Wright (1861-1935) and Eva Moltesen (1871-1934).

All of these came all from the middle classes – typically independent women, but with different political and religious backgrounds.

Tybjerg and Hansen were both school teachers and candidates for the Social-Liberal Party. Moltesen was an author and candidate for the Danish Liberals in 1918 (the very first election in Denmark in which women got the right to stand for Parliament and to vote). Daugaard was an editor. Wright was a philanthropist of a Christian background.

Despite these differences, the women engaged themselves in common activities for peace.

In 1916 they founded a Danish branch of Women’s Peace Party, Danish Women’s Peace Chain (Danske kvinder Fredskæde). They very successfully recruited members not just from among their peers, but also from the typically social-democrat women of the working class, including Henriette Crone (1874-1933), chairperson of the Women’s Printing Union.

The Danish Women’s Peace Chain was not a pacifist movement.

In the journal Kvinden og Samfundet (“Woman and Society”) as well as in various pamphlets, it was made clear that the Peace Chain “isn’t an association opposed to the national defence”, and that the members “on a par with women in other countries will devote themselves to the duty of upholding the independence of their country”.

It is probably fair to define the movement as “defencist” – as expressed by the British historian, Martin Ceadel, i.e. accepting a Danish defence – but only in case of a breach of the peace from abroad.

The Danish peace movement had a tradition for such a policy of defensive neutrality.

Likewise, Fredrik Bajer (1837-1922), founder of Association for a Neutralized Denmark (Foreningen til Danmarks Nevtralisering) in 1882 and the later Danish Peace Movement (Dansk Fredsforening), was of the conviction that Denmark had to defend its neutrality by military means.

In a broader perspective, though, he had an optimistic view on progress and nurtured the almost evolutionary idea that wars were about to be replaced by legal disputes. Violent, military confrontations were concepts from a remote, barbaric past. But by the end of the 1800s, he still advocated for the need of safeguarding peace by military means.

As a consequence of the outbreak of the First World War, Bajer’s dream of peace was destroyed, and he withdrew from the peace movement.

Yet, the Danish Peace Movement lived on and – quite tragicomically – ended up in a harsh dispute with the newly established association, when a number of members criticised the foundation of Danish Women’s Peace Chain.

For several years, this battle was fought through the columns of Fredsbladet (the “Peace Journal”) in a barrage of arguments for and against one united or a number of smaller movements.

Even as late as 1918 Henriette Beenfeldt (1878-1949) wrote, “Through the Danish Peace Movement we will seriously hinder our common noble aim if we don’t stop the discussion about this very soon and hereafter with sympathy look upon the foundation of the new movements, let alone the fact that such approach will serve us to a much greater honour”.

In short, neither the Danish Peace Movement nor Danish Women’s Peace Chain were basically pacifist movements and, at least from the outset, didn’t question the general conscript as did the syndicalists and members of the National League of Consistent Antimilitarists.

Other politicians also argued against war, such as the liberal politician Peter Munch (1870-1948) who advocated the solution of conflicts through parliamentary negotiations, arbitration and disarmament. Both he and the liberal internationalism, as pointed out by the Danish historian Karen Gram-Skjoldager, supported the rise of the pacifist movements in Europe and Russia through their antimilitarism.