Considered by many one of the founding texts of the science fiction genre, The Blazing World — via a dizzy mix of animal-human hybrids, Immaterial Spirits, and burning foes — tells of a woman’s absolute rule as Empress over a parallel planet. Emily Lord Fransee reflects on what the book and its author Margaret Cavendish (one of the first women to publish using her own name) can teach us about empire, gender, and imagination in the 17th century.

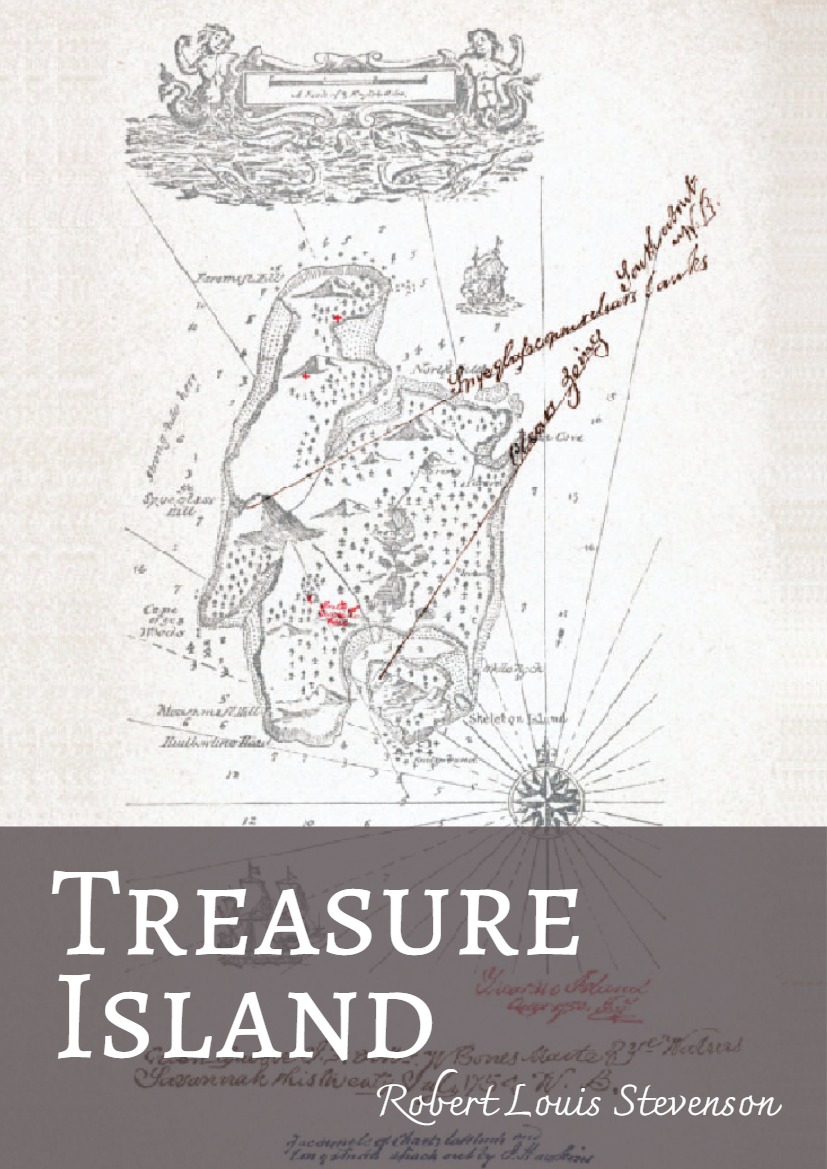

It is the middle of the seventeenth century and a Bear-man is helping an empress attempt to examine a whale through a microscope. After this task is found to be impossible, a group of Worm-men explain how creatures can exist without blood and how cheese turns to maggots. In her turn, the empress scolds an assembly of Ape- and Lice-men for their pursuit of tedious and irrelevant knowledge, such as the true weight of air, and commands they instead get busy with “such Experiments as may be beneficial to the publick”. Armed with such knowledge of the natural world and equipped with the resources of her vast dominions, she then sends flocks of Bird-men and navies of Fish-men to a parallel planet to make war on and conquer her many enemies.

Such are the links between life, learning, and power within The Description of a New World, Called The Blazing-World, a piece of prose fiction published in 1666 by the “Thrice Noble, Illustrious, and Excellent Princesse the Duchess of Newcastle”, better known as Margaret Lucas Cavendish. The narrative blends utopian fiction, imperialist travelogue, and natural history to tell the story of a “young Lady” who is kidnapped from her homeland but soon escapes to a new and mysterious land filled with human-animal hybrids. On arrival she is made empress and quickly establishes societies of natural philosophy, funds theater and the arts, and destroys her enemies with fire and fury.

The plot is often convoluted, with descriptions of military invasion or discussions with fantastical chimeras interspaced with short lessons on lenses or lectures on the nature of solar eclipses. Yet there is much that can be learned from Cavendish’s Blazing World, including the way it sheds historical and literary light on conceptions of gender, natural philosophy, political theory, theology, and the life of the author herself in seventeenth-century Europe. For example, in the emphasis on the stability of a realm in which everyone —- from the lowest Flea-man to the highest Emperor —- knows and respects their place in the natural hierarchy, we can see echoed Cavendish’s Royalist sympathies. Histories of feminism have also mined Cavendish’s works, as they reveal the ways in which she saw her own position limited within a society shaped by both gender and class. However, less examined is the way that the narrative illuminates the history of seventeenth-century European imperialism, and how ideas about power, race, and conquest related to those of gender and knowledge.

In considering the imperialist resonances of The Blazing World, it is helpful to start with Cavendish herself, an aristocratic philosopher poet whose reputation was divisive while she was still alive. A brief look at her published works indicates the range of her intellectual interests: poetry collections, a play entitled A Comedy of the Apocryphal Ladies, and scientific works such as Observations on Experimental Philosophy (1666), the latter of which originally included The Blazing World as an appendix of sorts. She was the first woman to attend a meeting of the Royal Society, where the all-male assembly protested her very presence. Of her visit, Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary that she was a “good comely woman; but her dress so antic and her deportment so unordinary, that I do not like her at all, nor did I hear her say anything that was worth hearing.”1 Her unusual wardrobe was a frequent focus of society commentary, cropping up again in English writer John Evelyn’s recollection of a visit to the Duchess that left him “much pleased with [her] extraordinary fanciful habit, garb, and discourse”, as well as her “extravagant humour and dress, which is very singular.”2 Her “singular” clothing choices played with conceptions of gender as well: her penchant for masculine waistcoats contrasting with one notable incident in which she addressed the audience at one of her husband’s plays while wearing a self-designed dress based on ancient Cretan costumes that left her breasts “all laid out to view.”