Canada’s Colorblind Chronicler and his Connecticut Exile

Abigail Walthausen explores the life and work of Arthur Heming, the Canadian painter who — having been diagnosed with colourblindness as a child — worked for most of his life in a distinctive palette of black, yellow, and white.

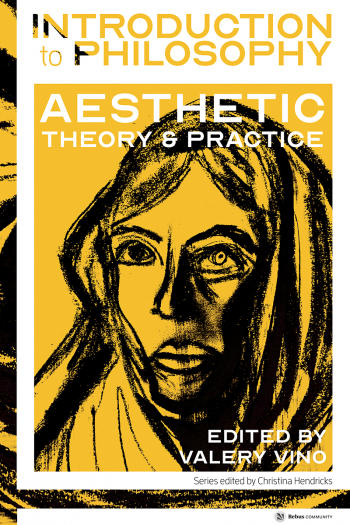

For most of his life, Arthur Heming, “painter of the great white north”, painted in a monochrome scheme of black, white, and yellow tones, choosing this style at least nominally because of an early diagnosis of color blindness. These possibly self-imposed restrictions lasted inexplicably until the age of sixty, when a full, nearly technicolor palette suddenly splashed across his canvases. Thematically, he worked with scenes whose colors were appropriately blanched: winter hunting and trapping expeditions that he took for the Hudson Bay Company and alongside people of the First Nations. His narrow focus in painting mirrored his work as a traveler, novelist, and illustrator, and the commercial nature of his output certainly influenced the mixed reception he received in the art market. In Canada he existed as an outsider of both the trapping communities he traveled with in the north and of his peers in the fine art world. His best work is transcendent, calling to mind the rich velvety grayscale of Gerhard Richter’s realistic paintings, while his weakest work is the sort of mystic wolf lore that later became the vernacular of furry bedspreads and black crewneck sweatshirts. Heming was conflicted about both his place in his homeland and his status as an artist. This is perhaps why he was so eager to find an adopted home for many consecutive summers in a distinctively non-arctic landscape, a farming community on the Long Island Sound, Old Lyme Connecticut.

While the Florence Griswold artist colony in Old Lyme Connecticut is generally touted as the “birthplace of American Impressionism”, Heming left a few distinctively Canadian marks on the communal dining room. First, there is his contribution to the collection of panels painted by artists who resided there; his, which depicts a lone canoe flying over rapids as seen from above, stands out from the rest because of its stark black and white color scheme and the narrow focus of its detail. Rather than a miniature painting of the pastoral Connecticut landscape, his seems like a snapshot of a larger, wilder, uncontainable narrative.

Both Heming’s work and his image are featured in Henry Rankin Poore’s 1905 frieze-like painting Fox Chase. All of the colony’s frequent residents appear in this painting as caricatures of their roles in the community. Childe Hassam is depicted shirtless and playing a prank, while Mathilda Brown, the sole female painter in the group, is filled with ladylike shock. Heming himself is depicted as a proper Canadian mountie, standing above the action. So while Heming’s painting sticks out like a sore thumb, his own caricature blends quite nicely into the scene depicted. He is both part of the community and an observer.

Abigail Walthausen is a writer and high school English teacher. She writes about technology and teaching the humanities at Edtech Pentameter.