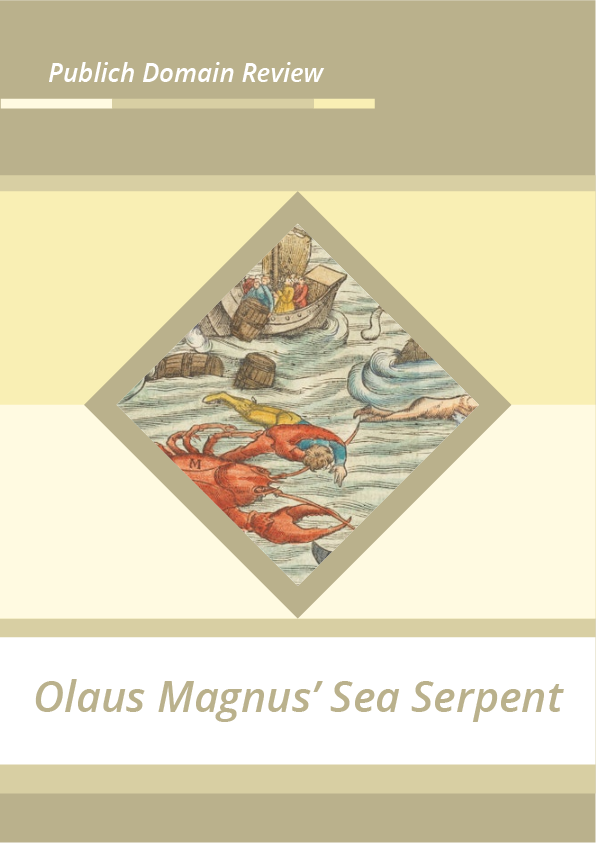

The terrifying Great Norway Serpent, or Sea Orm, is the most famous of the many influential sea monsters depicted and described by 16th-century ecclesiastic, cartographer, and historian Olaus Magnus. Joseph Nigg explores the iconic and literary legacy of the controversial serpent from its beginnings in the medieval imagination to modern cryptozoology.

In his comprehensive study, The Great Sea-Serpent: An Historical and Critical Treatise (1892), Dutch zoologist Antoon Cornelius Oudemans lists more than three hundred references to the notorious sea monster in his chronological “Literature on the Subject”. The first ten of those, 1555-1665, cite Olaus Magnus’ sea serpent: editions of Olaus’ Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (“History of the Northern Peoples”) and natural histories of Conrad Gesner, Ulisse Aldrovandi, Edward Topsell, and John Jonston. The list establishes Olaus’ serpentine monster as the major ancestral source of sea serpent lore from the sixteenth century to widespread sightings of such creatures in Oudemans’ own time. It is the basis for illustration and discussion of the creature in marine studies and popular fantasy up to the present, five hundred years after Olaus created it.

While Oudemans cites natural histories in which copies or variations of Gesner’s famous woodcut of Olaus’ sea serpent appear, his list does not refer to the monster’s iconic source: the 1539 Carta Marina. Oudemans had not seen the map. After it went out of circulation by the 1580s, it was lost for three centuries until a copy was discovered in the Munich state library in 1886, shortly before publication of The Great Sea-Serpent. A second copy surfaced in 1962 and is now in the Uppsala University Library. The wall map, measuring about 5 feet (1.5m) wide and 4 feet (1.2m) high, was the largest, most accurate, and most detailed map of Scandinavia––or of any European region––at that time. A Catholic priest exiled with his Archbishop of Uppsala brother, Johannes, from their native Sweden after it converted to Lutheranism, Olaus began compiling the nationalistic map in Poland in 1527. Created to show the rest of Europe the rich history, culture, and natural wonders of the North prior to the Reformation, the map was printed in Venice twelve years later.

The northern seas of the marine and terrestrial map teem with fantastic sea monsters either drawn or approved by Olaus. The most dramatic of those, off the busy coast of Norway, below the dreaded Maelström, is the great serpent, coiling around a ship’s mast and lunging with bared teeth at a sailor on the deck. Like the map’s other sea beasts, the serpent is not just a cartographical decoration to fill space, as in Jonathan Swift’s “elephants in wont of towns.” It is meant to represent a real animal, one that Nordic sailors and fishermen vividly described to Olaus on his travels around Scandinavia. The Latin legend accompanying the image indicates the monster is 300 feet (91.4m) in length. According to the map’s key, on the other hand, it is “A worm 200 feet long wrapping itself around a big ship and destroying it.”

Since publication of The Book of Gryphons in 1982, Joseph (Joe) Nigg has explored the rich cultural lives of mythical creatures in a variety of styles and formats for readers of all ages. Sea Monsters: The Lore and Legacy of Olaus Magnus’s Marine Map was published in 2013 by Ivy Press in the United Kingdom and as Sea Monsters: A Voyage Around the World’s Most Beguiling Map by the University of Chicago Press in the United States.