The Smile in Portraiture

Why do we so seldom see people smiling in painted portraits? Nicholas Jeeves explores the history of the smile through the ages of portraiture, from Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa to Alexander Gardner’s photographs of Abraham Lincoln.

Today when someone points a camera at us, we smile. This is the cultural and social reflex of our time, and such are our expectations of a picture portrait. But in the long history of portraiture the open smile has been largely, as it were, frowned upon. In Charles Dickens’ Nicholas Nickleby (1838-39) the portrait painter Miss La Creevy ponders the problem:

…People are so dissatisfied and unreasonable, that, nine times out of ten, there’s no pleasure in painting them. Sometimes they say, “Oh, how very serious you have made me look, Miss La Creevy!” and at others, “La, Miss La Creevy, how very smirking!”… In fact, there are only two styles of portrait painting; the serious and the smirk; and we always use the serious for professional people (except actors sometimes), and the smirk for private ladies and gentlemen who don’t care so much about looking clever.

A walk around any art gallery will reveal that the image of the open smile has, for a very long time, been deeply unfashionable. Miss La Creevy’s equivocal ‘smirks’ do however make more frequent appearances: a smirk may offer artists an opportunity for ambiguity that the open smile cannot. Such a subtle and complex facial expression may convey almost anything — piqued interest, condescension, flirtation, wistfulness, boredom, discomfort, contentment, or mild embarrassment. This equivocation allows the artist to offer us a lasting emotional engagement with the image. An open smile, however, is unequivocal, a signal moment of unselfconsciousness.

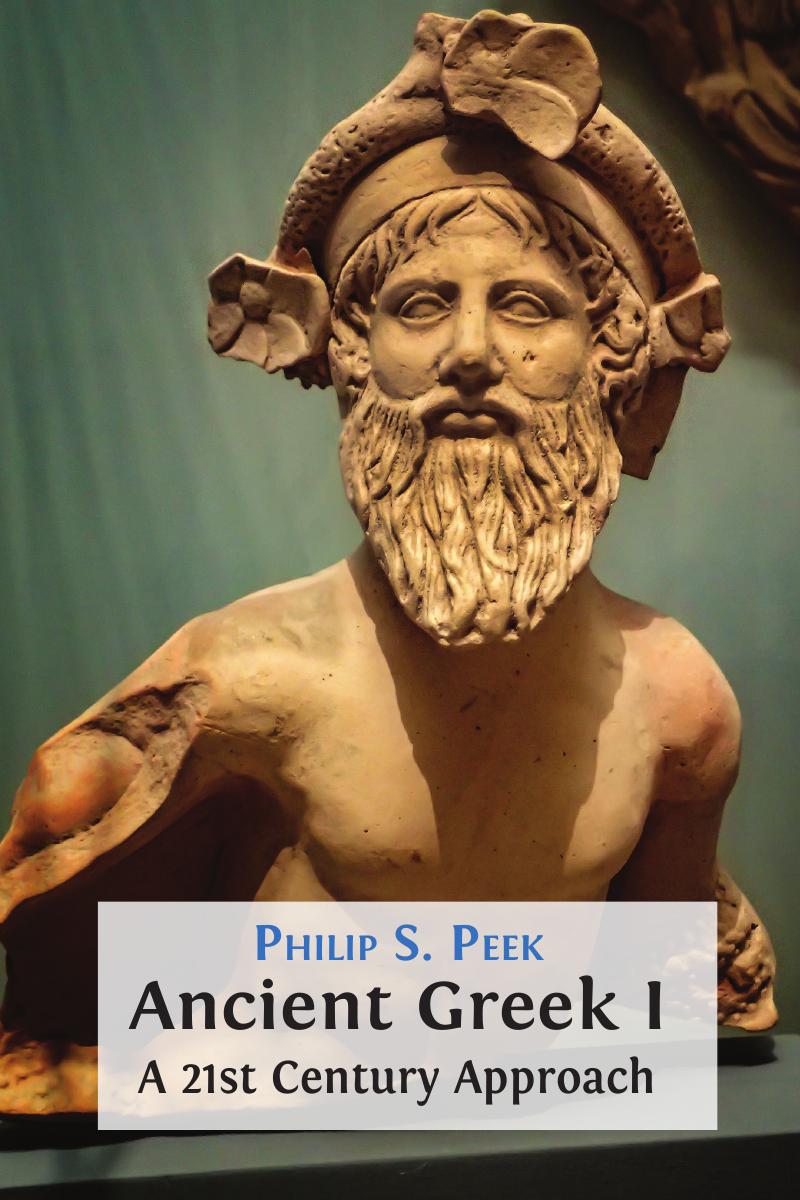

Such is the field upon which the mouth in portraiture has been debated: an ongoing conflict between the serious and the smirk. The most famous and enduring portrait in the world functions around this very conflict. Millions of words have been devoted to the Mona Lisa and her smirk – more generously known as her ‘enigmatic smile’ — and so today it’s difficult to write about her without sensing that you’re at the back of a very long and noisy queue that stretches all the way back to 16th century Florence. But to write about the smile in portraiture without mentioning her is perverse, for the effect of the Mona Lisa has always been in its inherent ability to demand further examination. Leonardo impels us to do this using a combination of skilful sfumato (the effect of blurriness, or smokiness) and his profound understanding of human desire. It is a kind of magic: when you first glimpse her, she appears to be issuing a wanton invitation, so alive is the smile. But when you look again, and the sfumato clears in focus, she seems to have changed her mind about you. This is interactive stuff, and paradoxical: the effect of the painting only occurs in dialogue, yet she is only really there when you’re not really looking. The Mona Lisa is thus, in many ways, designed to frustrate — and frustrate she did.

Nicholas Jeeves is a designer, writer, and lecturer at Cambridge School of Art. He is also designer and editor of Lucian’s Dialogues of the Gods, a new edition of Lucian’s comic masterpiece out now on PDR Press.