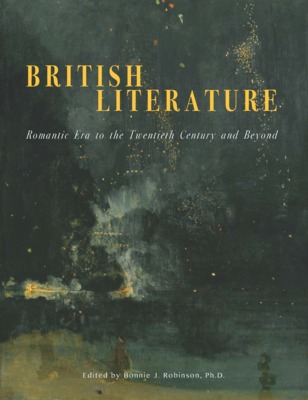

The Romantic Era

As a literary movement in England, Romanticism could be said to have fired its first salvo in 1801 with William Wordsworth’s (1770-1850) “Preface” to the Lyrical Ballads. Lyrical Ballads is a collection of poetry that Wordsworth co-published with Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834). The term “Romanticism,” describing this movement, came after the fact. Romanticism lasted until the mid-1820s, with the deaths of the poets Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) and George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824).

In his preface to Hernani (1830), Victor Hugo wrote that “Romanticism was nothing more than liberalism in literature.” Romanticism can be considered a rebellion against the conservative thought and literature of the eighteenth-century Age of Reason, a period that looked to ancient Rome and classical forms for models of perfection. The eighteenth-century Age of Reason was politically conservative and monarchic; other features, especially in terms of literature, include decorum, conventionality/ models, harmony, artificiality, logic, and objectivity. Romanticism is neither romance nor the desire for prettiness or sentimentality; instead, it is closer to being anti-eighteenth century, or a repudiation of what went before. The idea of liberalism, to which Hugo referred, is expressed in the Romantic desire for an egalitarian (as opposed to monarchic) government, and for the freedom of the individual.

This revolutionary spirit was inspired by actual revolutions, including the American Revolution (1775-1783) and the French Revolution (1789-1790s). These revolutions occurred within a wealth of intellectual thought and new ideas on what were human rights and what role government and society played in securing these rights. Some influential works were Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s The Social Contract (1762), which questioned the efficacy of existing political systems; Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), which considered the consequences of revolution to the status quo; and Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man (1791-92), which suggested that all humans possessed inherent rights, rights that governments could potentially or actually threaten. Universal human rights existed independently of people’s social position, or class. They considered the qualities that all humans shared, regardless of family, history, or income. The Romantics thought that all humans shared emotions and imagination. For the Romantics, these qualities served to validate human equality.

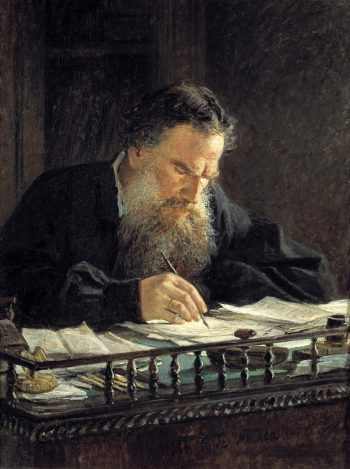

Romanticism regarded as values subjectivity and individuality—indeed, individual subjectivity. It shifted the eighteenth century’s focus on outward action to a new focus on inward action, that is, to action in the mind. Romantic literature scrutinized feelings and the relation of feeling to the outer world. Sincerity, openness, transparency, and spontaneity allowed that relationship to be more apparent, and the lyric, or song-like expression of an individual’s emotions, became a characteristic Romantic genre. The imaginative individual created from the external impressions of natural beauty and human civilization an ideal of perfection within themselves, the embodiment of which they then sought to find in the external world. The Romantic image—of the skylark, nightingale, midnight frost—epitomizes their quest for a union of the organic and the imaginative (through imaginative perception). The “closet drama,” or dramas not intended to be (or even able to be) performed, and the historical novel, in which time and place could be conflated, were genres well-suited to Romantic expression. Related qualities of the unformulated, or innocent; the unconscious; and the mysterious (and even “exotic”) actuated Romantic focus on, or interest in, children, and the child-like; nature, and those perceived as being close to nature, like agricultural workers; and the imaginative, or the poet.