On 24 October 2020, it will be 50 years since rich countries committed to spending 0.7% of their gross national income (GNI) on aid to low- and middle-income countries. The gross national income (GNI), previously known as the gross national product (GNP), is the total domestic and foreign output claimed by residents of a country, consisting of gross domestic product (GDP), plus factor incomes earned by foreign residents, minus income earned in the domestic economy by nonresidents. Comparing GNI to GDP shows the degree to which a nation’s GDP represents domestic or international activity. GNI has gradually replaced GNP in international statistics. While being conceptually identical, it is calculated differently.GNI is the basis of the calculation of the largest part of contributions to the budget of the European Union.

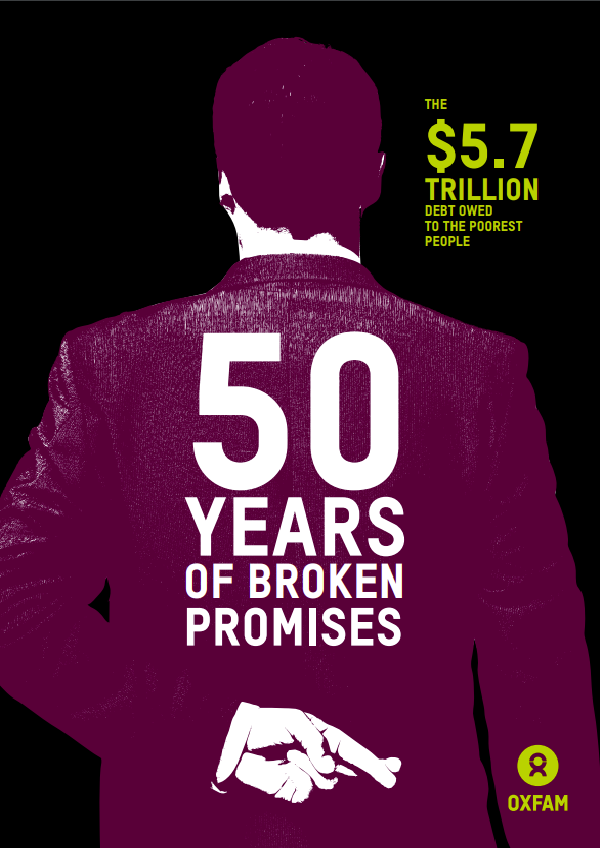

This paper examines how aid has helped to improve the well-being of people in low- and middle-income countries. It discusses how donors’ broken promises on the 0.7% target have limited the potential of aid to reduce poverty and inequality. Oxfam has calculated that in the 50 years since the 0.7% promise was made, high-income countries have failed to deliver a total of $5.7 trillion in aid. Finally, this paper reflects on the future of aid.

International aid is a crucial tool in the fight against poverty and inequality, and it is the only rich-country policy that puts the people living in poverty around the world first. Aid is also a form of redistribution between countries; this redistribution is a moral imperative in a world where global inequality has reached extreme levels, due in large part to past and ongoing exploitation of many countries by a handful of wealthy nations. Furthermore, aid is one of the only ways to channel additional financing to the budgets of low- and middle-income countries, where it is essential to boost investment in public goods and social spending. Seven countries in subSaharan Africa, for example, fund their social protection programs entirely through international aid.

As the decades have passed, however, high-income countries have time and again missed deadlines and broken their aid promises. Oxfam has calculated that in the 50 years since the 0.7% promise was made, donor countries have failed to deliver a total of $5.7 trillion in aid. Essentially, this shortfall means that the world’s richest countries owe a $5.7 trillion debt to the world’s poorest people. This figure is nine times larger than Sub-Saharan Africa’s stock of external debt at the end of 2019 ($625 billion). For the human development that has been lost as a result of donor countries’ inaction, there is also an immeasurable moral debt to pay.

These trillions in unpaid aid could have helped eradicate hunger and extreme poverty. It would cost, for instance, an estimated $4.8 trillion over planned expenditures during 2019–2030 to meet all 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)7 in the world’s 59 lowest-income countries. The financing gap for achieving the health SDG worldwide is estimated at $3.9 trillion between 2016 and 2030.

Instead, today, there remains a very long way to go. Before the coronavirus pandemic, nearly 3.3 billion people lived below the $5.50 per day poverty line. The number of people suffering from chronic food insecurity has risen since 2015; an estimated 2 billion people do not have regular access to safe, nutritious, and sufficient food. The dramatic impact of COVID-19 is making a dire situation worse; the pandemic could push 121 million more people into an acute hunger crisis this year, and in worst-case scenarios could undo decades of progress by forcing an additional 226 million to half a billion people into poverty.